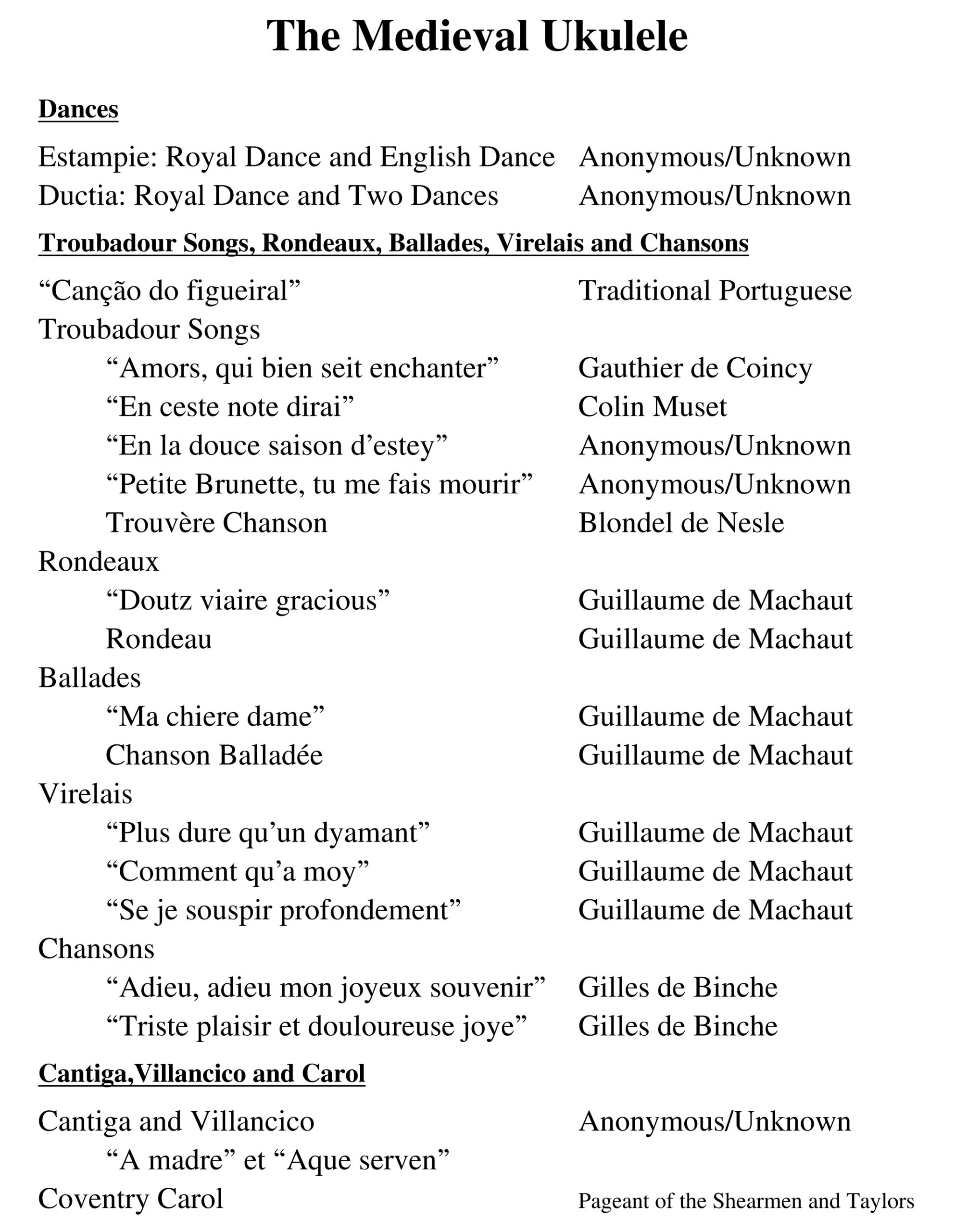

The Medieval Ukulele is now available on Amazon and Kobo. Here are the explanations of the arrangements and links to the recordings so you can explore the music from the 5th to 15th centuries …

Author archives: Robert Vanderzweerde

Older Posts on Facebook

This blog is starting today (October 25, 2020) but there have been posts about Ancient Music for Ukulele since June 7, 2018. A selection of older posts will be re-posted on this blog page (back dated to the original post date). The remainder will be skipped but you can still view them on Facebook at www.facebook.com/ancientmusic4ukulele

What’s Next – Medieval music

A Branle Dance (with real dancers)

Special Promotion

My “healed” Ukulele

My uke is healed and heading home from the hospital. Great job by Twisted Wood Guitars, based here in Alberta, Canada.

My “sick” Ukulele

My poor sick and injured ukulele is in the “hospital” at Twisted Wood Guitars (where I bought it). The good news is that it is repairable and I should have it back soon. Thanks!

How I select the music to arrange?

I’ve been asked how I select the music to arrange. Well, I play through a lot of music that I can find (original folios or other arrangements) based on the theme of the book I’m working on. It certainly improves my sight reading skills. I then select based on playability (some pieces are much too difficult for my purposes but I don’t shy away from challenging music) and enjoyability in terms of being able to listen to the music and liking it. Less than half of what I explore meets these criteria.

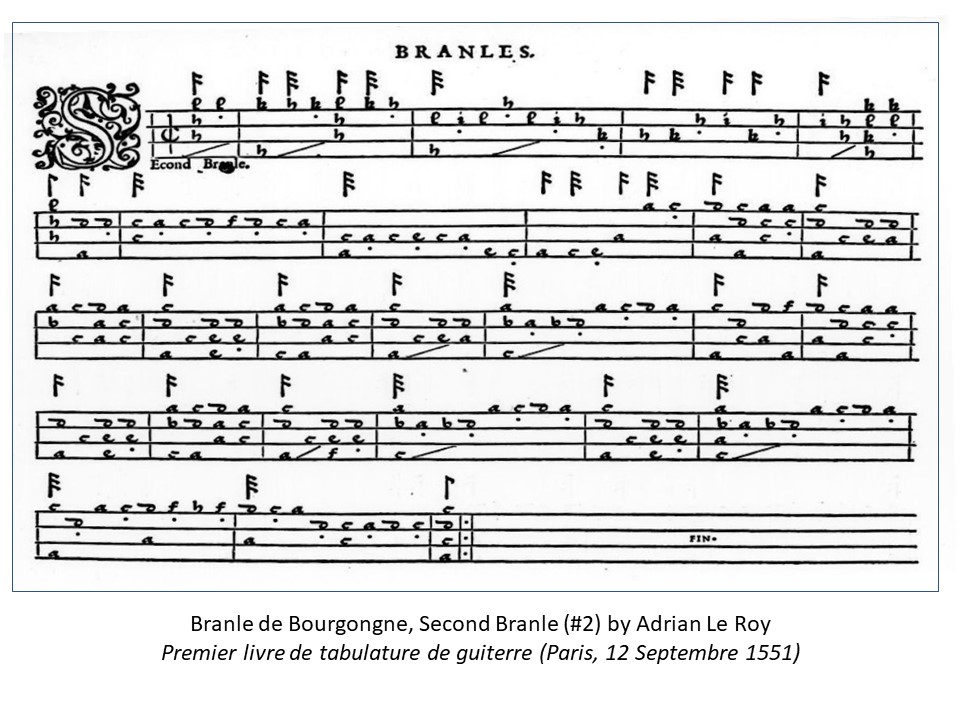

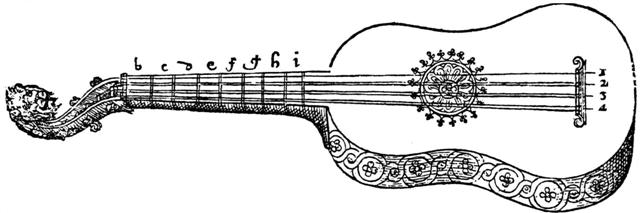

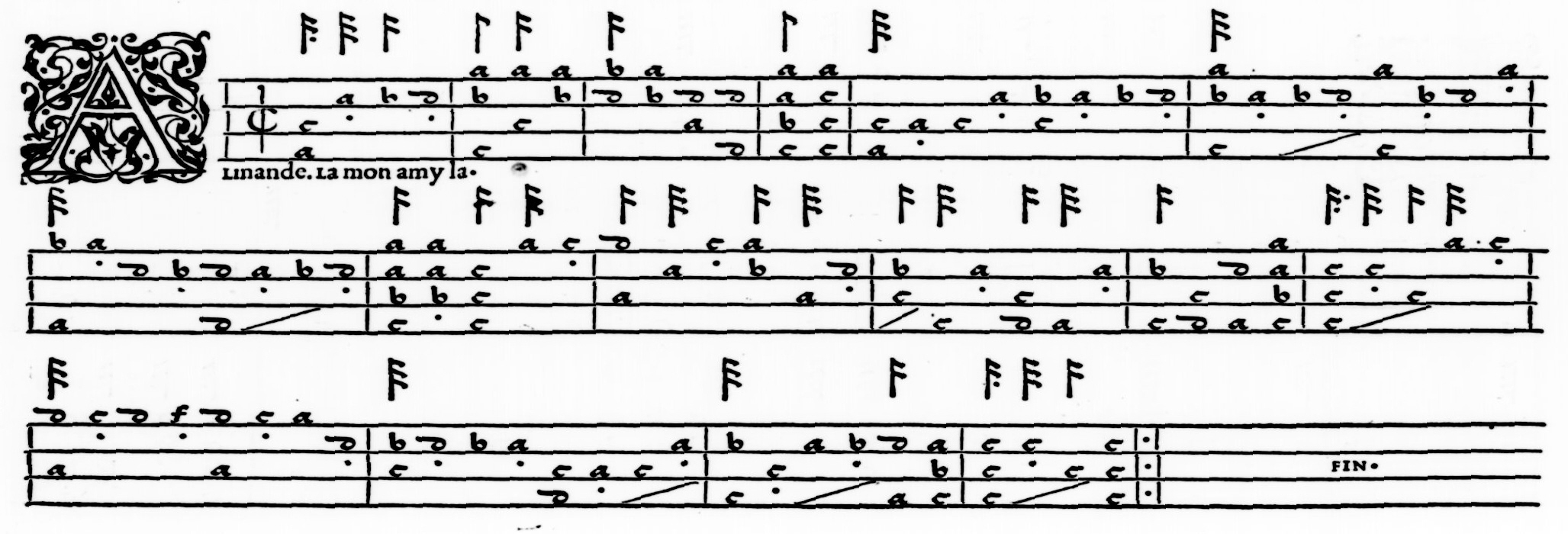

How does ancient tablature compare to modern musical notation and modern tablature?

How do you read ancient tablature?