There is literally a ton of music by Renaissance composers for the guitar, vihuela, lute and other stringed instruments (e.g. cittern and bandora).

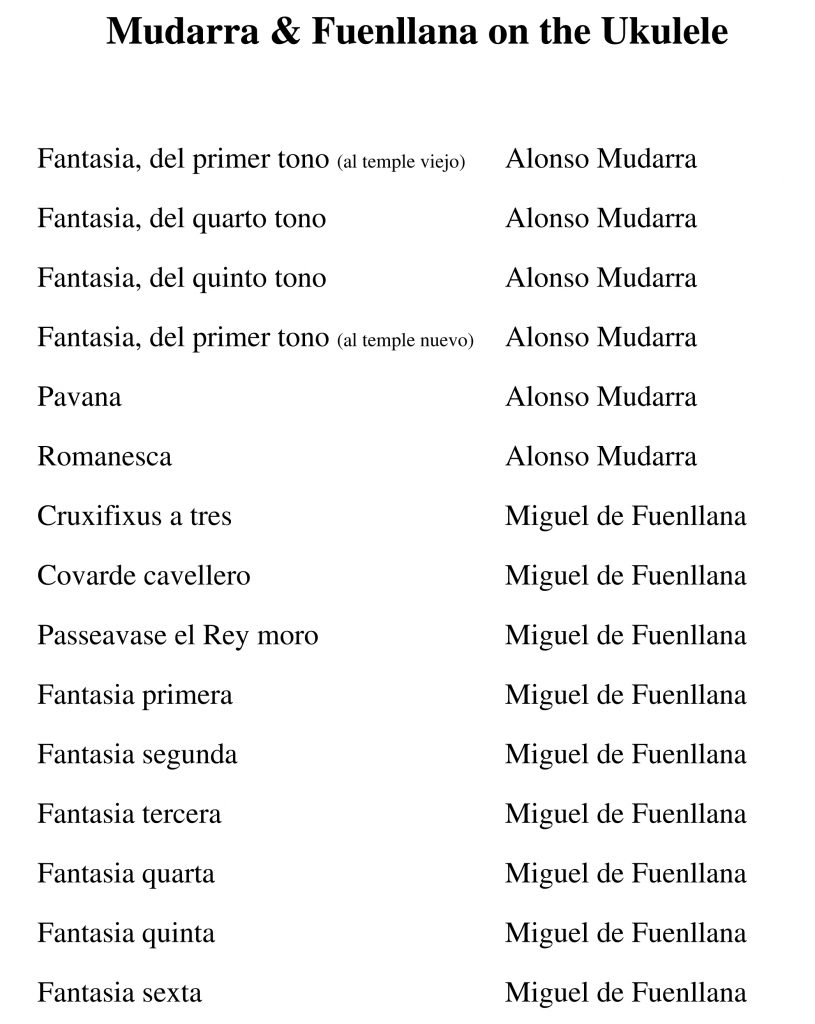

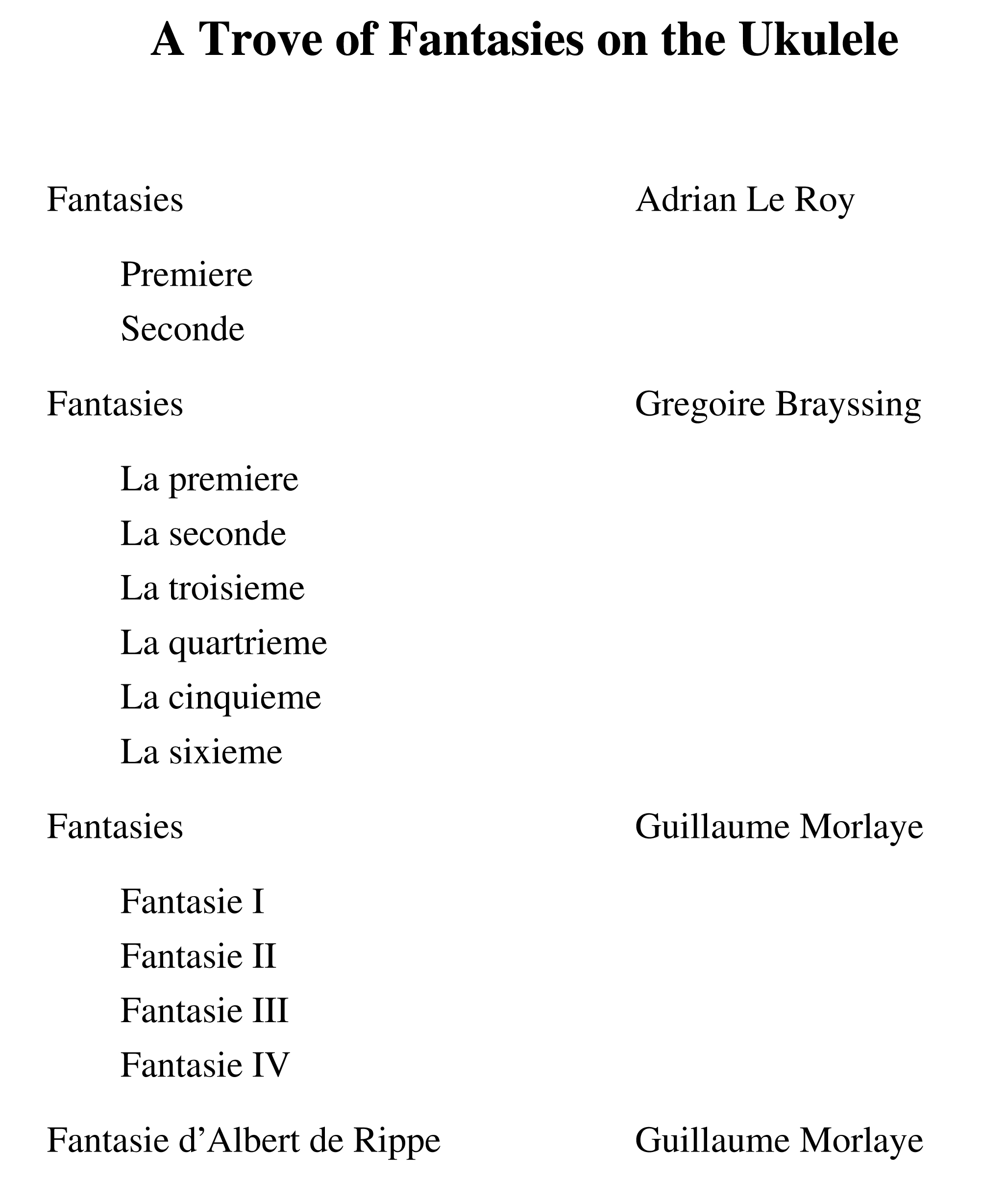

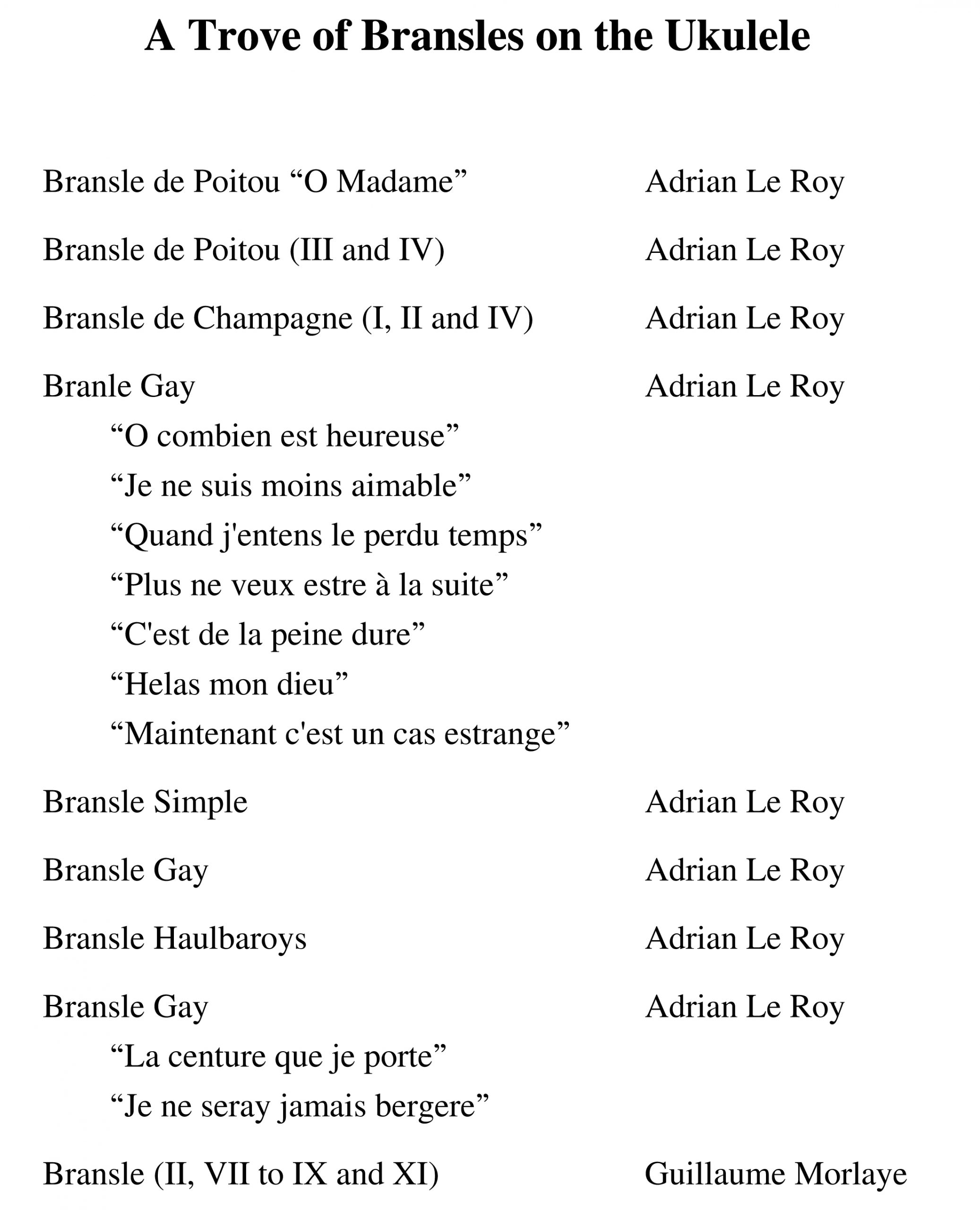

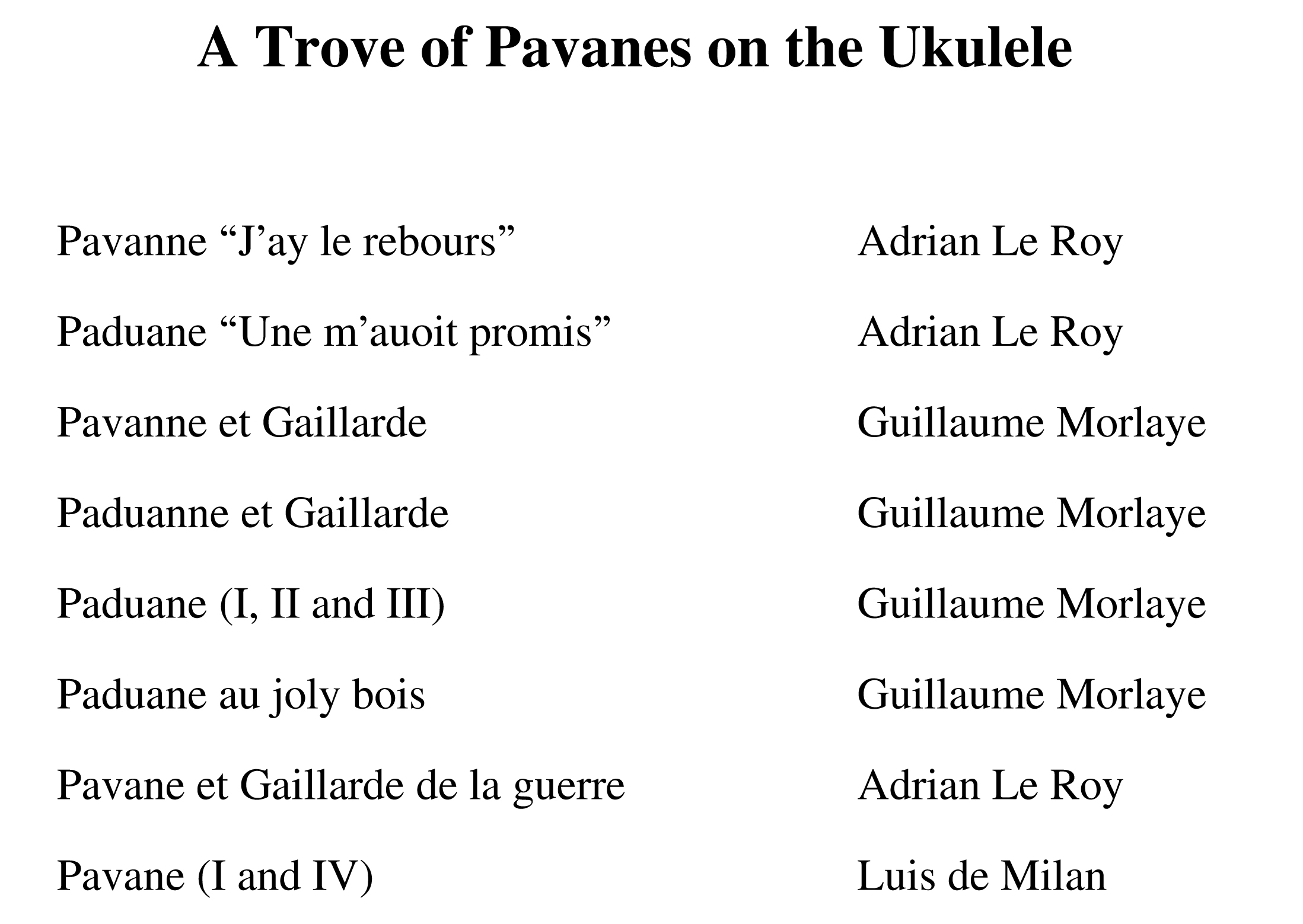

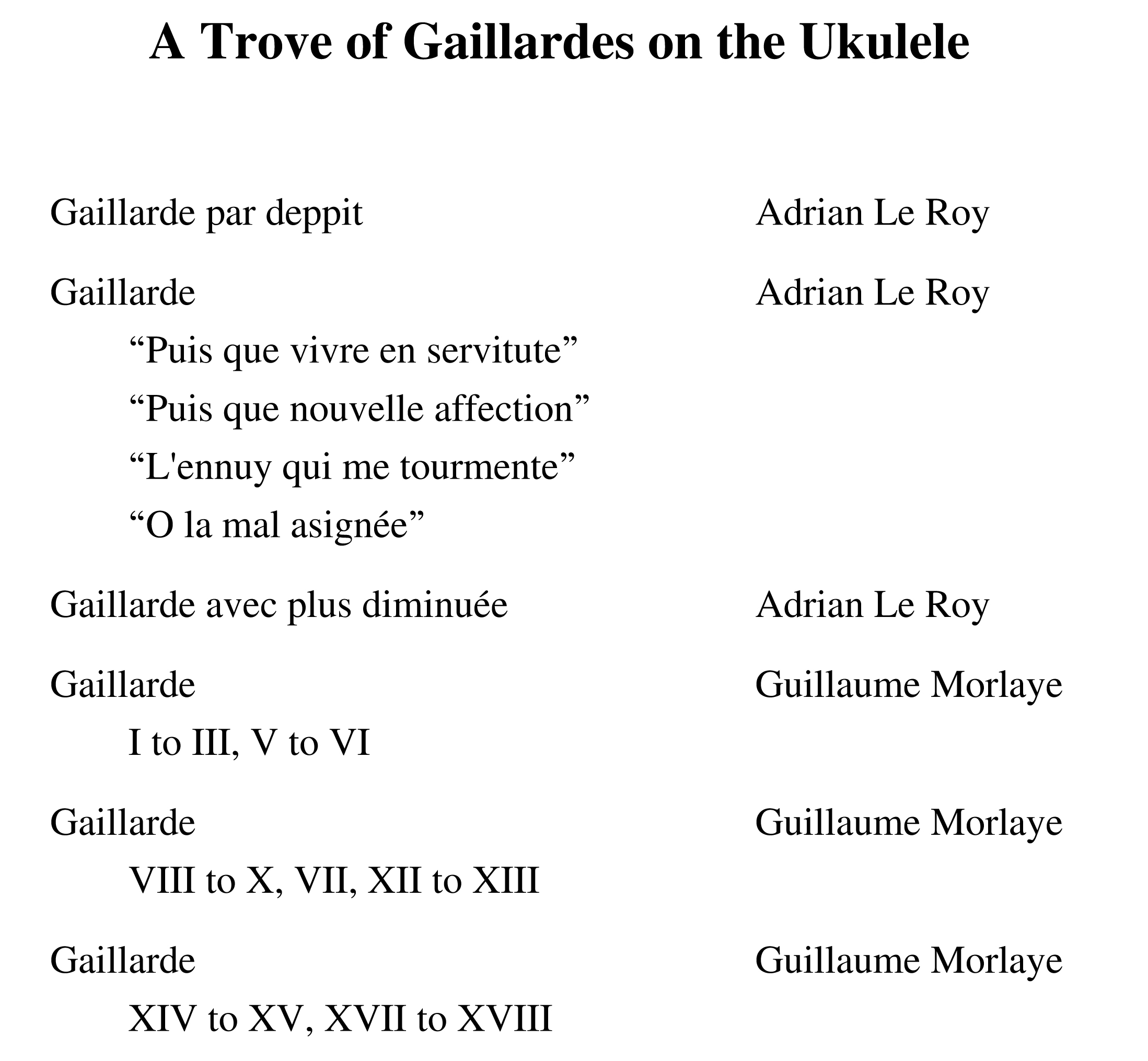

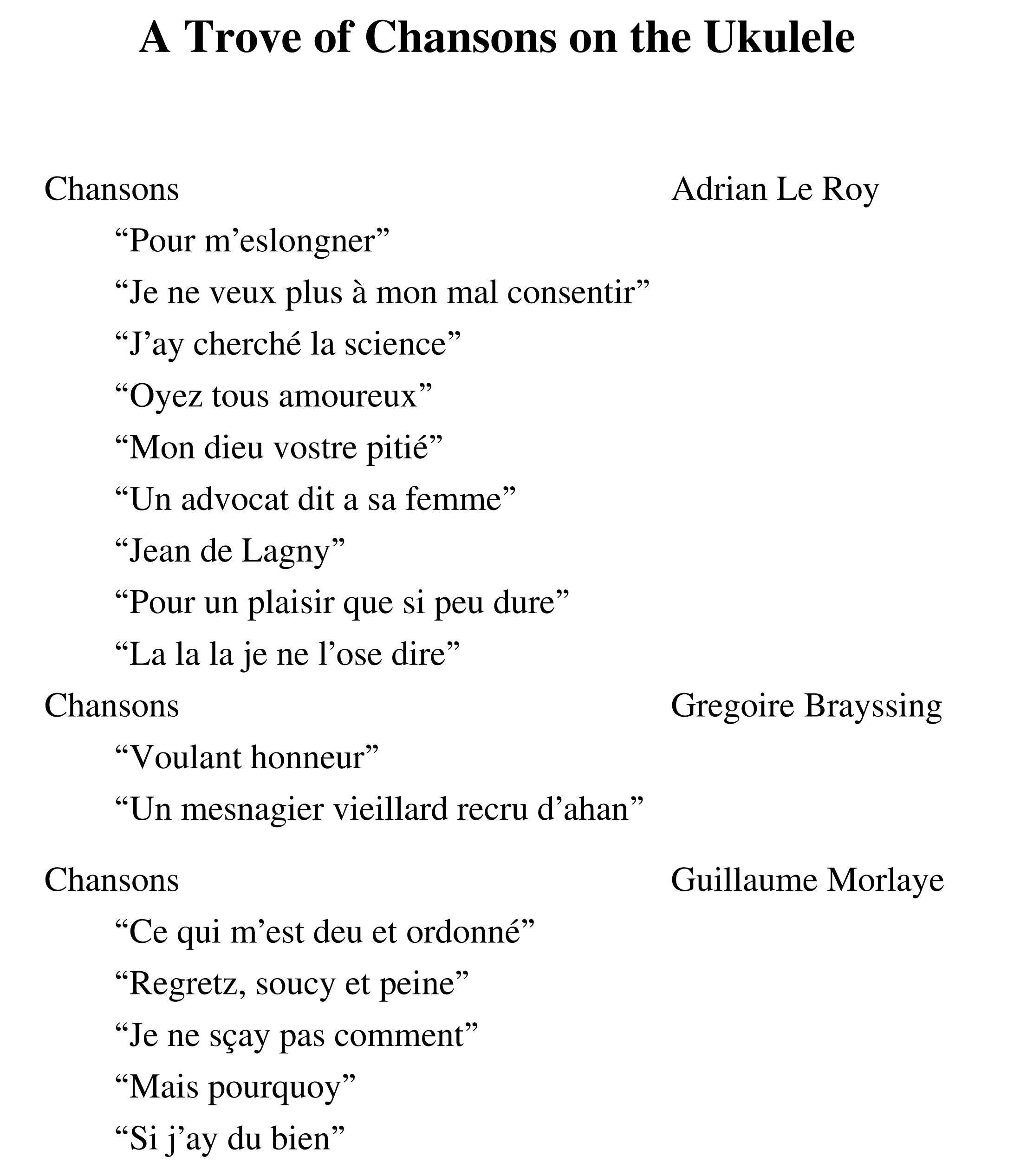

So far, I’ve arranged most of the guitar music (Renaissance guitar that is) of:

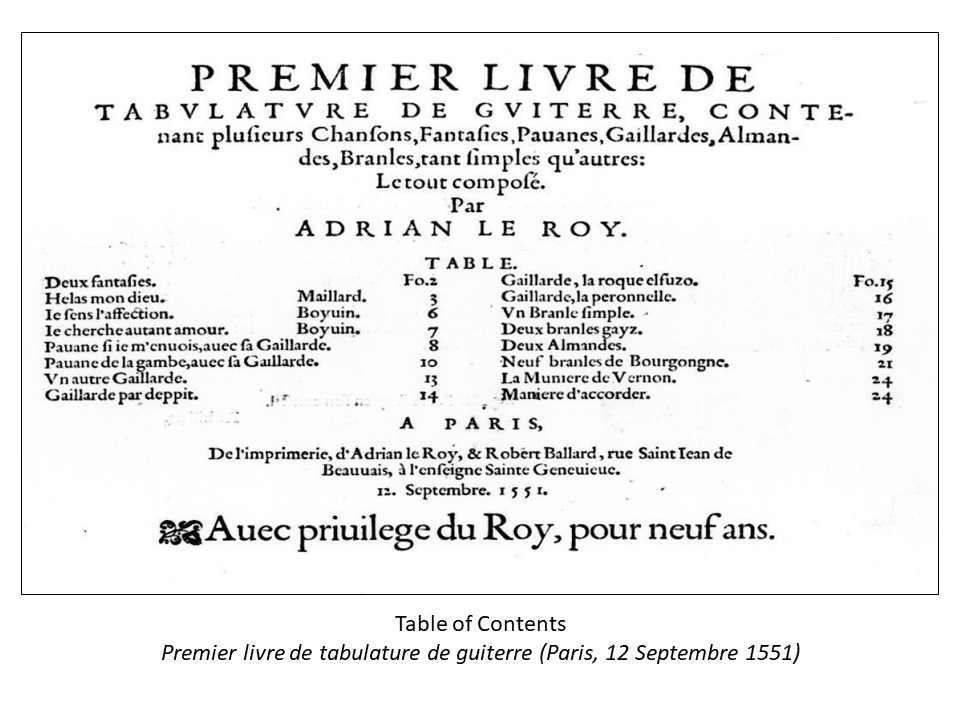

- Adrian Le Roy (ca 1520 – 1598)

- Guilluame Morlaye (ca 1510 – 1558)

- Gregoire Brayssing (flourished 1547 – 1560)

- Simon Gorlier (flourished 1550 – 1584)

- Jacques Arcadelt (ca 1507 – 1568)

- Alonso Mudarra (ca 1510 – 1580)

- Miguel de Fuenllana (ca 1500 – 1579)

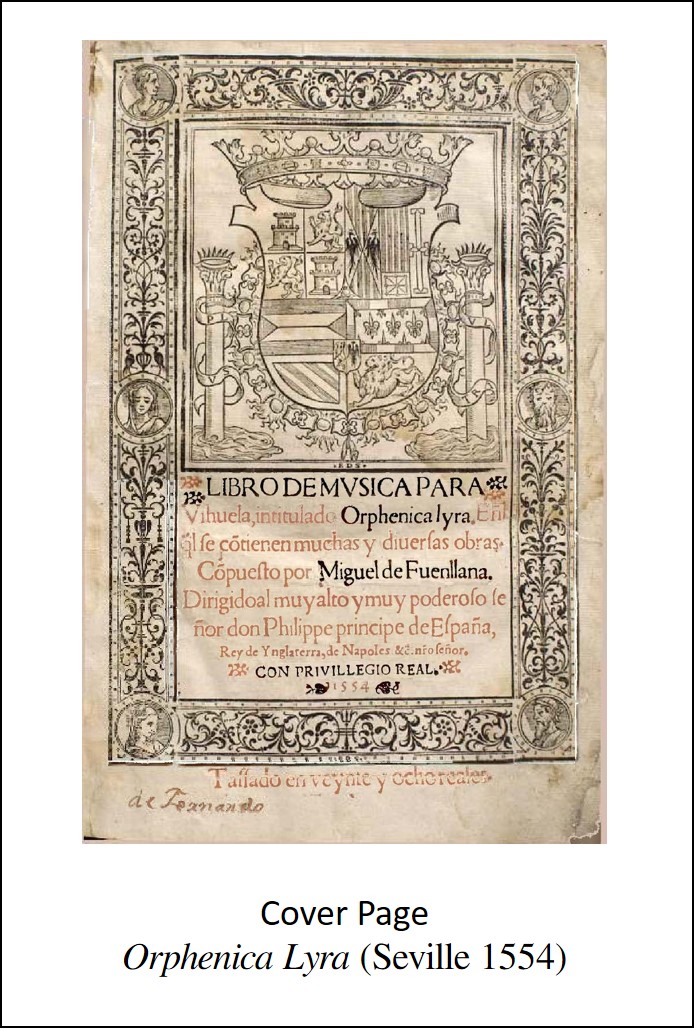

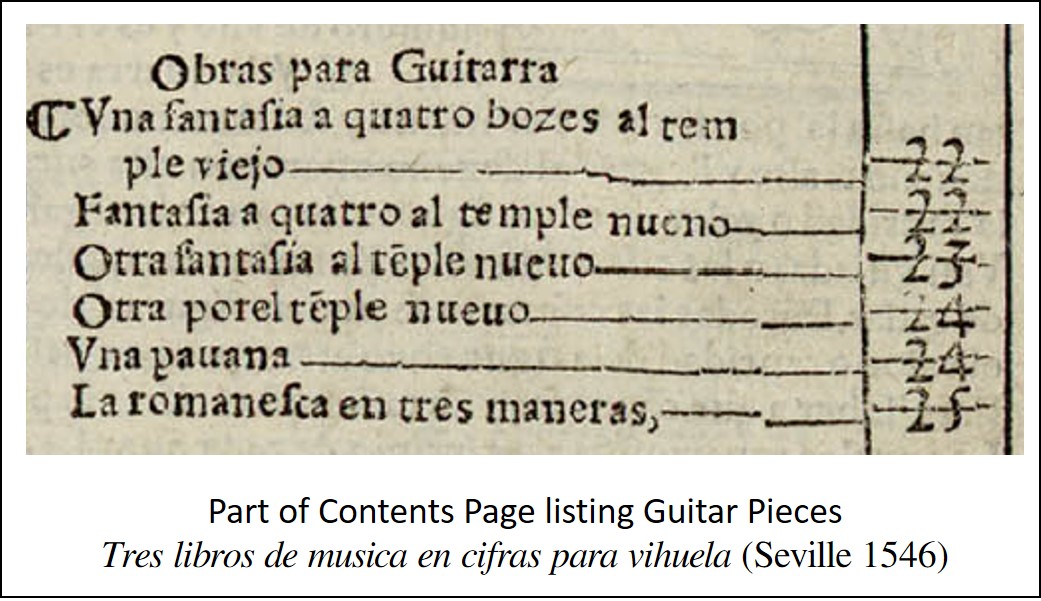

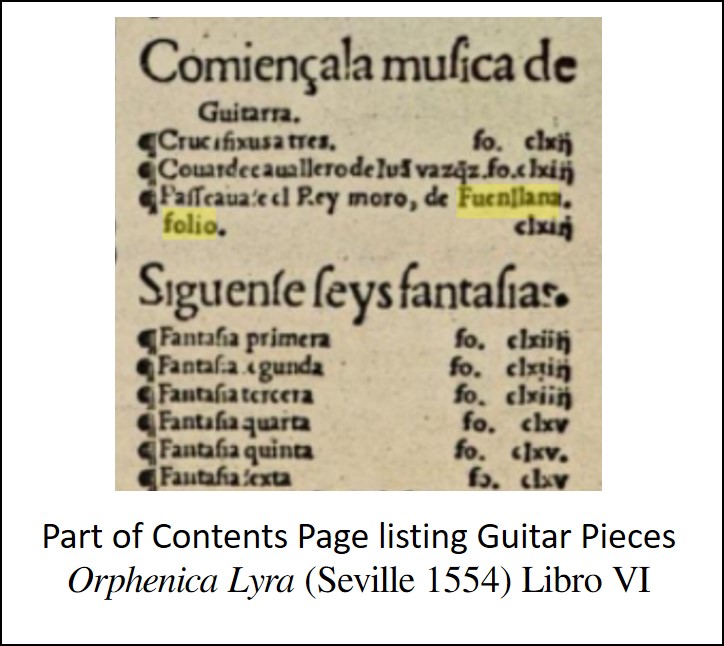

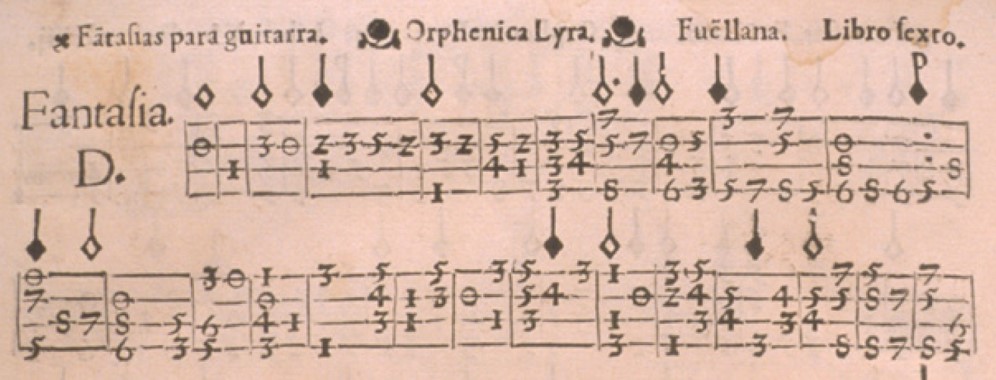

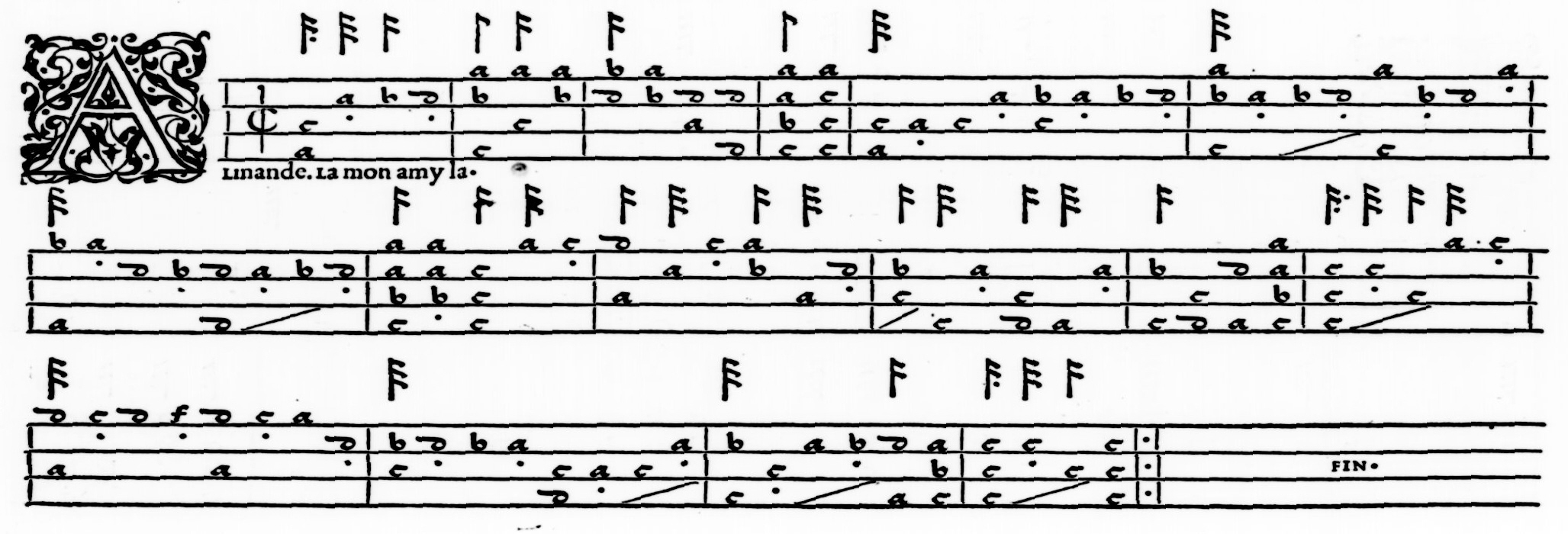

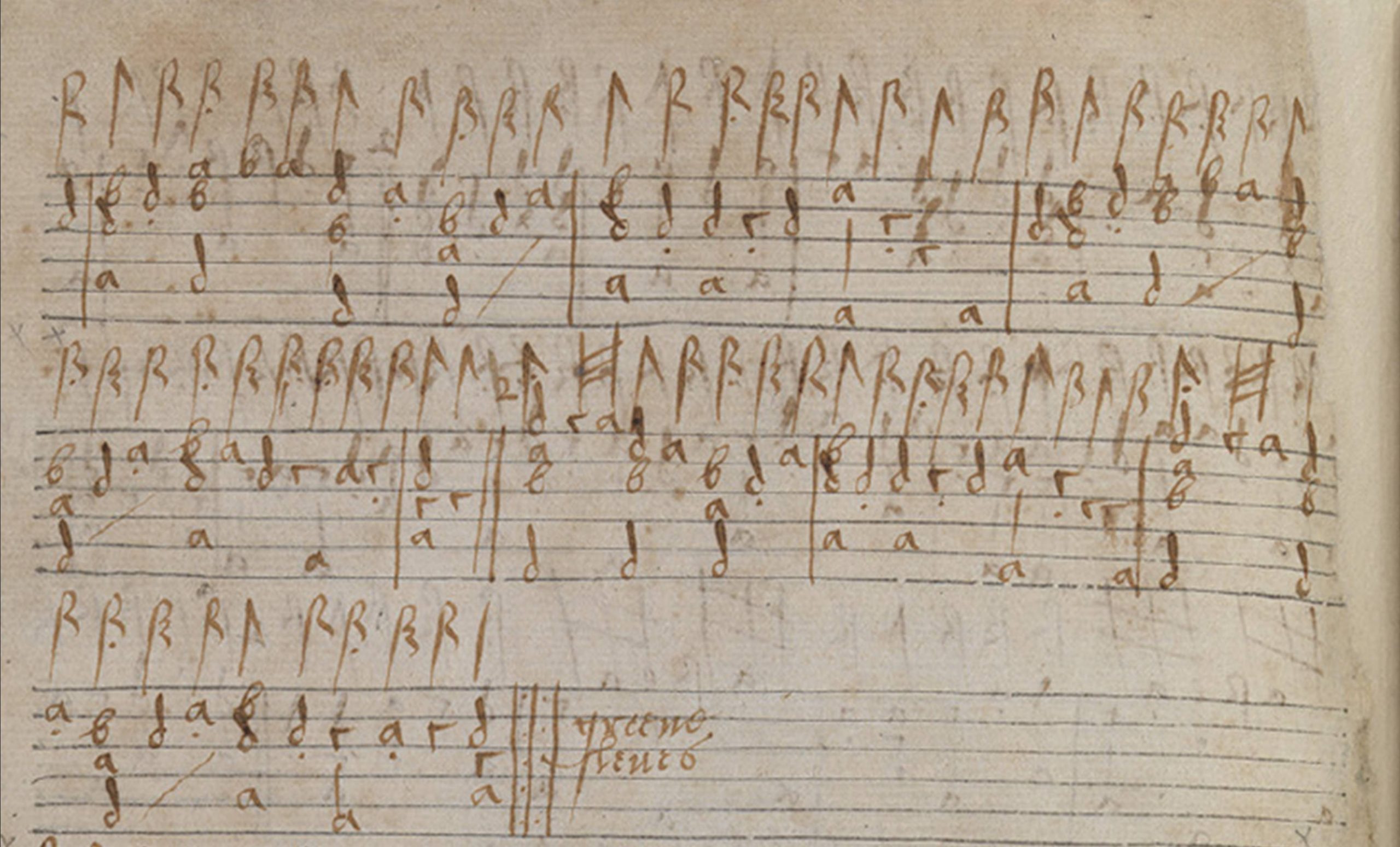

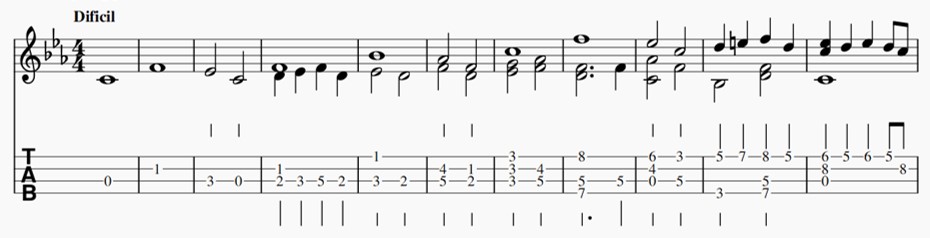

The music of these composers are in surviving printed music books which have been scanned and are available online. Images of the book covers and samples of the original music are included in the books of arrangements for ukulele that I have prepared (the arrangements are based on the original tabulature rather then guitar arrangements by others to avoid transcription issues).

While exploring other composers to arrange for ukulele, I am researching mainly vihuela and lute music. The Renaissance guitar had only a short period of popularity in the 16th century and it was overtaken by the Baroque guitar which was larger and had an extra string for a broader range of music and richer sound and resonance (which was then supplanted by the Romantic guitar and then by the modern classical guitar). The lute and vihuela have more strings (6 or more) and are tuned differently (e.g. G tuning on the vihuela with the third string tuned to F#, or later with Dm tuning for lutes in the Baroque era). The ukulele arrangements need to have adjusted bass notes, harmonics and key signatures in order to accommodate the 4-stringed ukulele with C tuning. Alternatively, a capo can be used to adjust the key signature. For example, if you strum the open strings on a ukulele, you are playing a C6 chord. If you strum the top four strings on a modern classical guitar, you are playing a G6 chord which becomes a C6 chord if you put a capo on the 5th fret.

So far, I have researched composers and/or original folios for the following Renaissance composers (see images of some of the book covers at the end of this post):

- Luis de Narváez (ca 1490 – 1547) – published book in six volumes for vihuela

- Francesco da Milano (ca 1494 – 1543) — four published books for vihuela

- Luys Milan (ca 1500 – 1562) — published book for vihuela (El Masetro)

- Miguel de Fuenllana (ca 1500 – 1579) — published book in six volumes for vihuela (with 9 guitar pieces)

- Alonso Mudarra (ca 1510 – 1580) — published book in three volumes for vihuela (with 7 guitar pieces)

- John Johnson (ca 1545 – 1594) — various lute books (e.g. Mathew Holmes)

- Anthony Holborne (flourished 1584 – 1602) — various books for lute, cittern, etc.

- Thomas Robinson (flourished 1589 – 1609) — various lesson books for lute, cittern, bandora, etc.

There are literally hundreds of pieces of music that can be arranged for ukulele. However, I do not plan to tackle them all and would like feedback on where to concentrate effort. For example, the six pavans by Milan are quite famous and I have already arranged two of them for solo ukulele and all six of them for ukulele quartet. Please comment on this post to let me know your thoughts. Much appreciated!